Chapter One

Dramatis Personae

On a very broad level, the Buddha and the German Romantics share two points of resemblance. Like the Buddha, the Romantics were born into a period of great social ferment: political, cultural, and religious. Like him, they were dissatisfied by the religious traditions in which they were raised, and they searched for a new way to understand and to cure their spiritual dissatisfaction.

There, however, the resemblances end. When we focus on specifics, the differences begin to appear. Some of the differences between the Buddha and the Romantics stem from differences in their respective environments: the precise nature of the social upheavals they experienced and the specific religious traditions that were dominant in their time and place.

In the Buddha’s case, the main social upheaval resulted from the rise of a monetary economy. Kings backed by moneylenders were expanding their realms, assuming absolute powers and absorbing small oligarchic republics into large centralized monarchies. At the same time, a wide variety of new religions arose, asserting the right of reason to question all the basic tenets of the Brahmanical religion and promoting a wide array of worldviews in its place. Some argued for a strict materialist deterministic view of the universe; others, a universe of total chaos; others, a universe in which human action played a role. Some taught the existence of an unchanging, eternal soul; others, that there was nothing in an individual that would survive death. In short, every position on the nature of the world, of the human being, and of the relation between the two was up for grabs.

In the case of the Romantics, however, the main social upheaval came from the French Revolution, which occurred when the Romantics were in their late teens and early twenties. The Revolution was something of a mirror image of the changes in the time of the Buddha, in that it attempted to replace the absolute rule of monarchies and oligarchies with a new order that would embody the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

As for religion, the Europe of the Romantics was much more monolithic than the Buddha’s India. One religion—Christianity—dominated, and most religious issues were fought within the confines of Christian doctrine. Even anti-religious doctrines were shaped by the fact that Christianity was the one religion with which they had to contend. The century prior to the Romantics had witnessed the rise of a rationalistic anti-Christian worldview, based on the mechanical laws discovered by Isaac Newton, but as the Romantics were gaining their education, new scientific discoveries, suggesting a more organic view of the universe, were calling the Newtonian universe into question as well.

In addition to political and religious upheavals, though, the Europe of the Romantics was also going through a literary upheaval. A new form of literature had become popular—the novel—which was especially suited to exploring psychological states in ways that lyric poetry and drama could not. Having been raised on novels, young Europeans born in the 1770’s tended to approach their own lives as novels—and in particular, to give great weight to exploring their own psychological states and using those states to justify their actions. As we will see in the next chapter, it’s no accident that the term “Romantic” contains the German and French word for novel, Roman.

For all the social differences separating the Buddha from the Romantics, an even greater difference lay in how they tried to resolve the spiritual dissatisfaction from which they suffered. In other words, they differed not simply because they were on the receiving end of different outside influences. They differed even more sharply in how they decided to shape their situation. Their proactive approach to their times explains a great deal about the differences separating their teachings.

There is something both fitting and very ironic about this fact. It’s fitting in the sense that the Buddha and the Romantics agreed on the principle that individual human beings are not merely passive recipients of outside stimuli from their environment. Instead, influences are reciprocal. People interact with their environment, shaping it as they are being shaped by it. What’s ironic is that even though the Buddha and the Romantics agreed on this principle, they drew different implications from it—which we will examine in Chapter Four—and they disagreed in action on how best to apply it to their lives, a point that we will examine here. Acting on their environments in different ways, they came to drastically different conclusions based on their actions—in particular, concerning how much freedom human beings have in choosing their actions, and how much freedom human action can bring about.

A few brief sketches of their lives will indicate what these differences were.

The Buddha

The version of the Buddha’s life most widely known in the West was first composed many centuries after his passing, when Buddhists in India wanted a complete biography of the founder of their religion. This was to fill in what they perceived as a lack in their tradition, because the earliest records—such as those in the Pāli Canon—contained glimpses of the Buddha’s life story only in fragmentary form.

However, the various biographies composed to meet this felt need didn’t simply fill in the blanks left by the fragments. Sometimes they introduced incidents that contradicted what the fragments had to say. A prime example is the story of the Buddha’s childhood. The later biographies presented a somewhat fairy-tale like story of a young prince, heir to a king, kept captive in the palace until after he is married, and who leaves the palace secretly in the darkness of night—after seeing for his very first time a sick person, an old person, a corpse, and a wilderness ascetic—in hopes that the life of an ascetic might lead to freedom from the facts of aging, illness, and death.

As told in the Pāli Canon, however, the events surrounding the Buddha’s decision to leave home and take up the life of a wilderness ascetic were much simpler and more realistic. In addition, they give greater insight into his character and the values that drove his quest.

These accounts carry a sense of immediacy in that they are told from the first person. In fact, they constitute one of the earliest spiritual autobiographies in recorded history. Because the Buddha’s central teaching was on the power of skillful kamma, or action, and the role of intention in shaping kamma, this is appropriate. In telling his listeners of what he did to attain awakening, and how this involved training his intentions to become more and more skillful, he was giving an object lesson in how they could develop the skills needed to reach awakening themselves.

In the Buddha’s telling, his father was not a king. Instead, he was an aristocrat, a member of the noble warrior caste, living in a small oligarchic republic—the type of society that was fast disappearing during the Buddha’s lifetime. The young bodhisatta, or “being in search of awakening,” was brought up in extreme luxury. Little is said of the education he received, but after he became Buddha he would illustrate his teachings with similes showing an intimate knowledge of the military arts and of music. And his skill at composing extemporaneous poetry shows that he was trained in the literary arts, too. Given the emphasis that the noble warrior caste placed on learning strategy and skills, it’s possible to see the influence of his original caste background on the Buddha’s eventual adoption of a strategic approach to the religious life as well.

With the passage of time, the bodhisatta came to feel great dissatisfaction with his situation. The texts describe his decision to leave the luxuries of his palaces—and to take up the path of a wilderness ascetic—as a result of three mind states.

The first is an emotion that in Pāli is called saṁvega, which can be translated as terror or dismay. The young bodhisatta was struck by an overwhelming sense of the futility of life in which people quarreling over dwindling resources inflict harm on one another only to die in the end.

I will tell of how

I experienced

dismay.

Seeing people floundering

like fish in small puddles,

competing with one another—

as I saw this,

fear came into me.

The world was entirely

without substance.

All the directions

were knocked out of line.

Wanting a haven for myself,

I saw nothing that wasn’t laid claim to.

Seeing nothing in the end

but competition,

I felt discontent. — Sn 4:15

The bodhisatta’s second mind state was a sense of sobering appreciation of the fact that he, too, would age, grow ill, and die just like the old, sick, and dead people that he had, up to that point, despised.

“Even though I was endowed with such fortune, such total refinement, the thought occurred to me: ‘When an untaught, run-of-the-mill person, himself subject to aging, not beyond aging, sees another who is aged, he is repelled, ashamed, & disgusted, oblivious to himself that he too is subject to aging, not beyond aging. If I—who am subject to aging, not beyond aging—were to be repelled, ashamed, & disgusted on seeing another person who is aged, that would not be fitting for me.’ As I noticed this, the (typical) young person’s intoxication with youth entirely dropped away.

“[Similarly with the typical healthy person’s intoxication with health, and the typical living person’s intoxication with life.]” — AN 3:39

The third mind state was a sense of honor. Given that life was marked by aging, illness, and death, he felt that the only honorable course would be to search for the possibility of something that didn’t age, grow ill, or die.

“And which is the noble search? There is the case where a person, himself being subject to birth, seeing the drawbacks of birth, seeks the unborn, unexcelled rest from the yoke: unbinding (nibbāna). Himself being subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement, seeing the drawbacks of aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement, seeks the aging-less, illness-less, deathless, sorrow-less, undefiled, unexcelled rest from the yoke: unbinding. This is the noble search.” — MN 26

By framing his goal as the “deathless,” the bodhisatta was following an old tradition in India. However, as we will see, he broke with tradition in the strategy by which he finally reached this goal.

The Canon states that, having made up his mind to search for the deathless, the bodhisatta cut off his hair and beard in his parents’ presence—even though they were grieving at his decision—put on the ochre robe of a wilderness ascetic, and went forth into the wilderness.

His search for awakening took six years. When later describing this search, he kept referring to it not only as a search for the deathless, but also as a search for what was skillful (MN 26). And he noted that his ultimate success was due to two qualities: discontent with regard to skillful qualities—i.e., he never let himself rest content with his attainments as long as they did not reach the deathless—and unrelenting exertion (AN 2:5). Although he described his feelings leading up to his decision to go forth, he claimed that from that point forward he never let the pains or pleasures he gained from his practice or from his career as a teacher invade or overcome his mind (MN 36; MN 137).

At first, he studied with two meditation teachers, but after mastering their techniques and realizing that the highest attainments they yielded were not deathless, he set out on his own. Most of his six years were spent engaged in austerities—inducing trances by crushing his thoughts with his will or by suppressing his breath, going on such small amounts of food that he would faint when urinating or defecating. When finally realizing that, although he had pursued these austerities as far as humanly possible, they gave no superior knowledge or attainment, he asked himself if there might be another way to the deathless. After asking this question, he remembered a time when, as a young man, he had spontaneously entered the first jhāna, a pleasant mental absorption, while sitting under a tree. Convincing himself that there was nothing to fear from that pleasure, he began eating moderate amounts of food so as to regain the strength needed to enter that concentration.

It was thus that he entered the path to awakening. On the night of his awakening, after attaining the fourth jhāna—a more stable and equanimous state—he gained three knowledges through the power of his concentration: The first two were knowledge of his own past lives and knowledge of how beings die and are reborn repeatedly, on the many levels of the cosmos, based on their kamma. The larger perspective afforded by this second knowledge showed him the pattern of how kamma worked: intentions based on one’s views and perceptions determined one’s state of becoming, i.e., one’s identity in a particular world of experience.

By applying this insight to the intentions, views, and perceptions occurring at the present moment in his mind, the Buddha was able to attain the third knowledge of the night: the ending of the mental states that led to renewed becoming. This was the knowledge that led to his attaining the deathless.

The key to his awakening lay in his revolutionary insight that the processes leading to becoming could be best dismantled by dividing them into four categories—stress or suffering (dukkha), the cause of stress, the cessation of stress, and the path of practice leading to the cessation of stress. Each of these categories carried a duty. Stress, he saw, should be comprehended to the point of developing dispassion for its cause. Its cause was then to be abandoned, so that its cessation could be realized. To do all of this, the path had to be developed. As he later said, only when he realized that all four of these duties had been brought to completion did he affirm that he was truly awakened.

This strategy of reaching the deathless by focusing on the problem of stress in the present moment constituted the Buddha’s radical innovation within the Indian religious tradition. The four categories he used in analyzing stress became known as the four noble truths, his most distinctive teaching.

The Buddha later used two formulae to describe the knowledge that came with true awakening. Although the two differ somewhat in their wording, the essential message is the same: Total release had been attained, there was nothing left in the mind that would lead to rebirth, and there was no further work to be done for the sake of maintaining his attainment.

“Knowledge and vision arose in me: ‘Unprovoked [uncaused] is my release. This is the last birth. There is now no further becoming.’” — SN 56:11

“My heart, thus knowing, thus seeing, was released from the effluent of sensuality, released from the effluent of becoming, released from the effluent of ignorance. With release, there was the knowledge, ‘Released.’ I discerned that ‘Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world.’” — MN 4

The Buddha then spent the next seven weeks experiencing the bliss of release: a release that was conscious but lay beyond the consciousness of the six senses—counting the mind as the sixth—and beyond the confines of space and time (§§46–47; DN 11). At the end of the seventh week, and at the invitation of a Brahmā, he decided to teach what he had learned about the path of awakening to others. Even though his mind had gone beyond pleasure and pain, he had not become apathetic. Quite the contrary: He devoted himself to establishing both a teaching and a monastic vehicle for preserving that teaching that would last for millennia.

There are a few poems in the Canon that are traditionally held to express the Buddha’s feelings on reaching awakening. For example:

Through the round of many births I roamed

without reward,

without rest,

seeking the house-builder.

Painful is birth again

& again.

House-builder, you’re seen!

You will not build a house again.

All your rafters broken,

the ridge pole dismantled,

immersed in dismantling, the mind

has attained the end of craving. — Dhp 153–154

Notice, however, that although this poem expresses a strong feeling of relief, it ends not with a feeling but with a fact: the end of rebirth has been attained through the ending of craving. Thus the poem teaches a practical message. And when we look at the Canon as a whole, we find that the number of passages expressing feelings about awakening are next to nothing compared to the number of passages where the Buddha teaches other people how to reach awakening, or at least to pursue the path to awakening, themselves. In other words, he focused on conveying the path as a skill for others to master. As he said, the things he came to know on awakening were like the leaves in a forest; what he taught—the four noble truths—was just a handful of leaves (SN 56:31). The leaves were chosen, he said, because they would be useful in helping others reach release. In other words, instead of expressing his feelings about the deathless, he focused on what can be called a more performative and descriptive style of teaching: i.e., using words that would have the effect of getting other people to want to practice for the sake of the deathless, and describing to them exactly how to go about doing it.

The Buddha spent the remaining 45 years of his life wandering over northern India, teaching the Dhamma and establishing a Saṅgha, or community, of monastic followers. In the first year, he trained a large number of men to become arahants, or fully awakened disciples, capable of teaching the Dhamma themselves. Then he returned to his home to teach his family. The Canon records that his son and several of his cousins eventually became arahants, and that his stepmother became the first member of the Saṅgha of nuns. The Commentary adds that his former wife and father became arahants, too. In this way the Buddha was able to provide his family with an inheritance much greater than anything he could have provided had he stayed at home.

Although the Buddha continued to meet with great success in leading others to awakening, his career was not without difficulties. Among them, there were the human difficulties of setting up Saṅghas—one for men, one for women—to provide a lasting system of apprenticeship whereby succeeding generations would be able to train in the Dhamma. There were also the difficulties of having to debate with members of rival sects who were jealous of his success and who didn’t always content themselves with debate: Sometimes they also leveled false accusations against the Buddha and the members of the Saṅghas.

There were also difficulties of a non-human sort. Having seen on the night of his awakening that beings can be reborn on many levels of the cosmos, he also realized that there is a being—called Māra—who exerts control throughout the realms of becoming, even to the levels of the highest gods (MN 49), and who jealously tries to prevent beings from gaining awakening and escaping his control. The Buddha also realized that Māra has allies within each unawakened mind in the shape of such unskillful qualities as sensual passion, craving, and hypocrisy. Māra had tempted the bodhisatta to give up his quest, and even after the Buddha’s awakening kept testing him—and his disciples—to see if their awakening was real.

In the face of all these difficulties, the Buddha acted with honor and dignity. Even on the day he was to pass away, he walked all day—after an attack of dysentery—from Pāva to Kusinarā so that he could teach the one last person he knew he had to teach. His final teaching, which he gave to that person, was the noble eightfold path, the same teaching with which he had begun his first sermon 45 years previously. Throughout his last day, he showed great nobility and calm: comforting his disciples, giving them one last chance to question him about their doubts concerning the teaching, even ensuring that the man who had provided the last meal that had brought on an attack of dysentery, instead of being reproached for the meal, would be praised for having given such a meritorious gift of food. After encouraging his disciples to achieve consummation in the practice through being heedful, he entered the various stages of concentration and then was totally unbound from becoming of every sort.

After seven days of funeral celebrations, his followers cremated his body. The relics were then enshrined in monuments in the major kingdoms of northern India. In the Theravāda tradition, the Saṅgha of monks that he established has lasted until the present day.

Five Early Romantics

When discussing the early German Romantics, one of the first problems is determining who counts as a member of the group and who doesn’t. Here our task is made somewhat easier by the fact that we are focusing on a specific aspect of early Romantic thought—Romantic views on religion—so we can limit our discussion to those Romantics who focused on issues of religion in light of the Romantic worldview.

The obvious candidates to include in any discussion of early Romantic religion are Friedrich Schleiermacher and Friedrich Schlegel, as they were the Romantics who wrote most prolifically on the topic. In fact, Schleiermacher’s Talks on Religion for Its Cultured Despisers (1799) was the first major book to treat religion from a Romantic standpoint. It is the defining text of Romantic religion.

Another obvious candidate for inclusion is Friedrich von Hardenberg, who is better known under his penname, Novalis. Novalis was Schlegel’s philosophical and literary partner in the years during which both of them worked out the implications of the Romantic worldview, and his ideas on the topic of authenticity seem to have been a major influence on Schleiermacher’s thought.

Two other candidates for inclusion are somewhat more controversial. One is Friedrich Hölderlin. Although his views on religion were very similar to Schlegel’s, he is sometimes excluded from the category of early Romantic on the grounds that he was only tangentially connected to the circle of friends who, during the late 1790’s, gathered in the university town of Jena at the home of August Schlegel, Friedrich’s brother, and to whom the appellation “Romantic” was originally applied. However, Hölderlin’s notebooks show that he was apparently the first German thinker to formulate what became the Romantic worldview. Also, the novel he published during his lifetime—Hyperion—contains many passages that deal with religious issues in line with that worldview. At the same time, his unpublished philosophical essays show that he worked out the religious implications of his worldview in many original ways, foreshadowing the thought of later thinkers, such as Carl Jung, who adopted and transmitted Romantic ideas on religion.

Hölderlin’s philosophical essays were not published until the middle of the 20th century, so it can’t be said that they were influential. Still, some of his religious views seem to have reached the Jena circle through Hyperion, through his poetry, and through conversation. At the same time, those views are of intrinsic interest in any history of Romantic religion in that they show how some of the strands of Romantic religion that came to light only much later were actually realized early on. So, for both of these reasons, he deserves to be included in the discussion here.

Another controversial candidate as an early Romantic religious thinker is Friedrich Schelling. Schelling was a member of the Jena circle, he had a strong influence on Schleiermacher and Schlegel, and he wrote extensively on religion himself, so it seems natural to include him as an early Romantic religious philosopher. The reason there would be some controversy around his inclusion is that there are two different criteria for determining who counts as an early Romantic philosopher and who doesn’t. Schelling meets one of the criteria, but not the other.

The one he doesn’t meet defines early Romantic philosophy by its style. Schlegel, Novalis, Hölderlin, and Schleiermacher all rejected the idea that an adequate description of experience could be built logically, like a building, on a foundation of rational first principles. After all, they sensed, there was so much in experience that was falsified as soon as it was expressed in a logical judgment. In particular, they believed that the most direct intuition of experience is that all Being is One. This intuition, however, cannot be adequately expressed in a sentence (or, as they called it, a judgment), even in the simple form of A = A, because judgments have to divide things before they can put them back together. For this reason, philosophy—which is composed of judgments—can approach the actual Oneness of experience only by approximation, without ever fully explaining or expressing it. As a result, instead of building philosophical systems, these four thinkers wrote philosophy in the form of dialogues, letters, novels, myths, and aphorisms. This style of philosophy is called anti-foundationalism.

Schelling, however, during the late 1790’s, was a foundationalist. He agreed that the most direct intuition of experience was that all Being is One, and that this experience could not be adequately expressed in a judgment. Still, he noted that even to say this much is to assume a great deal about experience. And for these assumptions to be persuasive, there was a need to show that they were consistent. To be consistent, he felt, they had to follow logically from a rational foundation. This was why, even though Schelling believed that philosophical systems couldn’t express everything, he saw a need to write philosophy in the traditional style: building systems—and he built many different systems during the late 1790’s—founded on the principle of A = A. Only in his later years did he become an anti-foundationalist himself. Thus on this criterion, Schelling would count as a late Romantic philosopher, but not as an early one.

However, there is another criterion for defining early Romantic philosophy, and that’s by its worldview. All five of these thinkers agreed that the universe is an infinite organic unity, and that human beings are integral parts of that unity. Because these thinkers also defined religion as an issue of the relationship of human beings to the universe, this seems the most relevant definition of Romantic philosophy when discussing Romantic religion. And because Schelling meets this criterion, he, too, deserves to be included in any discussion of early Romantic religious views.

We will present the cultural reasons for why the Romantics developed this worldview and this understanding of religion in Chapters Three to Five. Here we will briefly sketch their biographies to give an idea of some of the personal reasons for the way they arrived at Romantic religion.

We will start with Novalis first.

Novalis (1772–1801)

Georg Philipp Friedrich, Freiherr von Hardenberg, the only one of the early Romantics to come from a noble background, was born on the family estate in the Harz mountains to parents who were devout Pietists (see Chapter Three). He studied law in Jena, Leipzig, and Wittenberg. While at Jena, he read philosophy as well. This was during a period when one of the major issues at Jena was how to interpret Immanuel Kant’s philosophy. Kant had not built a philosophical system on first principles, and the issue for his interpreters came down to whether it should be rewritten so as to ground it with a first principle, to make it more complete, or left without a single foundation, to stay faithful to Kant’s style. Hardenberg’s tutors belonged to the anti-foundationalist camp.

In 1793, while at Leipzig, Hardenberg became friends with Friedrich Schlegel. The two began a correspondence that was to last, off and on, to the end of his life.

1795 was Hardenberg’s watershed year. He started reading the philosophy of Johann Fichte, a Kantian who proposed rebuilding Kant’s philosophy on first principles (see Chapter Three). At first he was taken with Fichte’s ideas, and this was one of his reasons for moving to Jena. There he met both Fichte and Hölderlin, who was studying under Fichte at the time. Later in that year, however, he started writing critiques of Fichte’s philosophy in his notebooks, gradually arriving at what was to become the Romantic worldview. (This was a common pattern among many of the early Romantics: At first enamored of Fichte’s philosophy, they ended up adopting the Romantic worldview in reaction to it.) Hardenberg in these early critiques also arrived at the basic Romantic view on genre: that this new worldview was best expressed through literature, rather than through academic philosophy.

On a more personal level, Hardenberg became engaged in March 1795 to Sophie von Kühn, who was only thirteen at the time. In September of that year, he entered the Mining Academy of Freiberg in Saxony, where he studied geology with Abraham Werner (see Chapter Three). In November, however, Sophie died, and Hardenberg spent many a night at her grave, mourning her loss. This experience led to an extravagant series of poems that were later printed as Hymns to the Night in 1800. A highly Romanticized version of Sophie, as the personification of wisdom, also became one of the main characters in a novel, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, which Hardenberg began writing toward the end of his life.

In 1796, he wrote to Friedrich Schlegel about his reasons for breaking with Fichte—reasons that also reflected the view of life he had developed in the course of mourning the loss of his fiancée.

“I feel more in everything that I am the sublime member of an infinite whole, into which I have grown and which should be the shell of my ego. Must I not happily suffer everything, now that I love and love more than the eight spans of space, and love longer than all the vacillations of the chords of life? Spinoza and Zinzendorf have investigated it, the infinite idea of love, and they had an intuition of its method, of how they could develop it for themselves, and themselves for it, on this speck of dust. It is a pity that I see nothing of this view in Fichte, that I feel nothing of this creative breath. But he is close to it. He must step into its magic circle—unless his earlier life wiped the dust off his wings.”1

Nevertheless, despite his break with Fichte’s philosophy, Hardenberg continued to be on good terms with Fichte the person. After meeting with him again in Jena in 1797, he wrote to Schlegel:

“At Fichte’s I spoke of my favorite topic—he did not agree with me—but with what tender consideration did he speak, for he held my opinion to be eccentric. This will remain unforgettable.”2

During this period Hardenberg started studying Platonic and Neo-Platonic philosophy, and in the winter of 1797–98 he printed—under the name, Novalis, which means “one who opens up new land”—the only philosophical work that he was to publish during his lifetime. The work, called Pollen, was in the form of short thoughts and aphorisms. The title is explained by the poem that serves as its epigraph:

“Friends, the soil is poor, we must sow abundant seeds

So that even modest harvests will flourish”3

In this book, Novalis—as we will call him from here on—formulated what were to be his most influential ideas: that freedom consists of learning to romanticize one’s life—to make it into a novel (Roman)—and that only a person who can accomplish this feat is truly authentic.

Toward the end of 1798, Novalis became engaged a second time, but the marriage never took place. The following year he started work as a manager of the salt mines in Saxony. Still, he found time to continue his philosophical and religious readings, in particular the writings of the mystic Christian, Jakob Böhme. He also commenced work on two novels—Heinrich von Ofterdingen and The Novices of Sais—but only the second was anywhere near completion when he died.

In 1800 he contracted tuberculosis, which was to prove fatal. During Novalis’ final illness, Schlegel reported having kept him well-supplied with opium—which was available in tincture form in those days—to ease his pain. As his end neared, Novalis had little strength even to read. As he wrote to a friend, “Philosophy lies next to me only in the bookcase.”4

After his death, Schlegel and the Romantic author Johann Ludwig Tieck published his novels. They also kept his poetry in print, and for many years Novalis’ reputation was primarily as an author and poet.

Another friend extracted passages from Novalis’ unpublished philosophical writings and printed them as a collection of fragments, but these left no great impression. Only in the 1950’s and 60’s were his philosophical essays edited and printed in their entirety. And thus it wasn’t until the middle 20th century that he came to be appreciated as a philosophical thinker of great breadth and originality.

Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829)

Born in Hanover, the youngest son of a Lutheran pastor, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel was apprenticed to a banker at an early age. Unhappy with this occupation, he pleaded successfully with his parents to be allowed to study law at the university in Göttingen, where his elder brother, August, was already studying the classics. The two brothers began to study aesthetics and philosophy together—Friedrich later commented that he read all of Plato in the Greek in 1788. From 1791 to 1793, he continued his study of law in Leipzig, where he met Novalis and Schiller.

While in Leipzig, Friedrich fell into a severe depression, from which he partly recovered when he decided to abandon law and to focus on philosophy and classical literature instead. Shortly thereafter, August, then in Amsterdam, asked Friedrich to act as a guardian to his mistress, Caroline Michaelis Böhmer (1763–1809), who was staying in Dresden. Caroline—a woman with a vivacious personality and striking intellect, and who later became one of the leading members of the Romantic circle in Jena—convinced Friedrich that he should try a career as a literary critic: a very uncertain profession in those days, but one that appealed strongly to Friedrich’s normally effervescent temperament. Once he had decided on this career path, his depression was fully gone.

He began writing and publishing reviews and literary essays. From 1794 to 1795, he championed classical literature against modern literature, but by 1796 his preferences began to shift in favor of the moderns.

A major inspiration for his shift was Fichte’s philosophy, which he had begun reading in 1795. As he later said, the main attraction in Fichte’s thought was the latter’s support of the French Revolution and the cause of freedom in general. In 1796 Schlegel traveled to Jena and met Fichte for the first time, which turned out in some ways to be a disappointing experience. Part of the disappointment was an issue of temperament. Schlegel, a person of broad interests, was surprised to learn that Fichte had no use for history or science. In one of his letters to a friend, Schlegel reported what was to become one of Fichte’s most famous utterances: that he would rather count peas than study history.

The other reason for Schlegel’s disappointment in Fichte was more philosophical. Fichte, in his eyes, was too much of a foundationalist. In another letter, Schlegel compared the “transcendental” aspect of Fichte’s philosophy—concerning principles of thought that transcended the senses—to the “transcendence” of a drunken man who climbs up on a horse but then transcends it and falls down on other side. Still, as was the case with Novalis, Schlegel’s philosophical disagreements with Fichte did not prevent them from remaining friends. For a while, in fact, his term for his favorite social activity—discussing philosophy in an open-ended manner with his friends—was to “fichtesize.”

To further his literary career, Schlegel moved to Berlin in 1797, where he attended the salons of Rahel Levin and Henriette Herz. There he met Schleiermacher and others who were later to become members of the Romantic circle in Jena. In fact, Schlegel’s friendship with Schleiermacher became so close that they shared a house with two other friends from 1797 to 1799.

It was in the Herz salon that Schlegel also encountered Dorothea Mendelssohn Veit (1764–1839)—the first woman he had met with anything like Caroline Böhmer’s intellect and charm. Dorothea, the daughter of the eminent Enlightenment philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (see Chapter Three), was trapped in a loveless marriage to a banker. In what was apparently a case of love at first sight, she and Schlegel began an affair. After obtaining a divorce from her husband in 1798, she moved in with Schlegel. The two did not become married, however, until 1804, because had they married before then she would have lost custody of the younger of her two surviving sons with Veit.

Based on the affair, Schlegel wrote a novel, Lucinde, which he published in 1799. Immediately denounced as pornographic, the novel provoked a storm of controversy in Berlin. By modern standards, there is nothing pornographic about the novel at all, and even by the standards of the time, the descriptions of lovemaking, though fervid, were very vague. What apparently offended the good people of Berlin was that the two main characters in the novel, Schlegel/Julian and Dorothea/Lucinde, were having an adulterous affair and yet were not punished at the end of the novel for their sins. Instead, the novel was an unapologetic celebration of a love presented as far more holy than formal matrimony.

The word “holy,” here, was not meant to be strictly metaphorical. Schlegel announced that he intended Lucinde to be the first of a series of books that would constitute a new Bible for modern times. However, as was to become a typical pattern in his life, he never completed the project. Still, Lucinde is an important document for the study of Romantic religion, and we will look more closely at its religious implications in Chapters Four and Five.

To escape the scandal in Berlin, Schlegel and Dorothea moved to Jena, where August—now married to Caroline—had become a professor at the university. There, at August and Caroline’s home, the “Jena circle” began to meet.

The core members of the circle were the Schlegel brothers and their wives, Schelling, Schleiermacher, Tieck, Clemens Brentano, and Sophie Mereau. Novalis would join their discussions when his work permitted, and even Fichte—who is best classed as a pre-Romantic—also met with them frequently. The members of the circle were quite young. Caroline Schlegel, at 36, was the eldest; Brentano, at 20, the youngest. Most, like Dorothea and Friedrich Schlegel, were in their late twenties. They met often, if on an irregular basis, to listen and respond to talks, to discuss what they had been reading, and to read their latest writings aloud to one another for feedback. Discussions ranged through philosophy, the sciences, culture, history, politics, and all the arts.

Historians have cited the Jena circle as a prime example of what can happen when a group of strong, lively intellects challenge one another—in an atmosphere of cooperation combined with competition—to develop their thoughts to a higher pitch of sophistication and originality than they might otherwise have reached had they been working in isolation. What they achieved as a group, even though they didn’t agree on everything, was to spark a revolution in Western thought.

Their meetings inspired Dorothea Schlegel to write to a friend in Berlin, “[S]uch an eternal concert of wit, poetry, art, and science as surrounds me here can easily make one forget the rest of the world.”5 Her husband, too, adopted a musical metaphor when he described Jena as a “symphony of professors.” And it was approximately during this period that he came up with a new term for the sociable, open-ended type of philosophical discussions in which the Jena circle excelled: “symphilosophy.”

During the years 1798–1800, the Schlegel brothers also published a literary journal, Athenäum. This journal was the primary vehicle through which the members of the Jena circle disseminated their ideas throughout the German-speaking world.

Friedrich Schlegel’s contributions were among the most provocative in the journal. In addition to essays, he composed fragments—pithy aphorisms and short passages, often ironic, playful, and self-contradictory—that covered a wide variety of topics in literature, philosophy, religion, art, politics, and culture in a style that contrasted sharply with the more formal and pedantic discussions of these topics in other journals. Schlegel’s fragments alerted the public to the fact that the Jena circle was engaged, not only in new thoughts, but also in new ways of thinking.

The Jena circle didn’t last long. Fichte was forced to leave the university in 1800, after refusing to apologize for what some of his detractors had denounced as atheistic elements in his philosophy. Friedrich Schlegel lectured in philosophy for one year in his place, but the lectures were poorly attended and his contract was not renewed. In 1803, August and Caroline Schlegel were divorced so that Caroline could marry Schelling (see below), but the controversy around the divorce proved so relentless that all three left Jena for good. With their departure, the early Romantic period effectively came to an end.

Meanwhile, Friedrich and Dorothea had begun an itinerant life. In 1802, they had moved to Paris, where Friedrich studied Sanskrit and edited journals in German reporting on the arts in Paris. In 1804, the couple moved to Cologne, where he studied Gothic architecture and lectured privately on philosophy. Through these years, Dorothea engaged in translation work, which was apparently what kept the couple solvent during their wanderings.

The year 1808 saw two events that marked Friedrich’s public break with his Romantic period. The first was the publication of the results of his Sanskrit studies, On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians. This book, which praised Sanskrit as the original language whose excellence had led directly to the excellence of the German language, sparked a long-term interest among German scholars in Indian studies. However, despite its praise of Sanskrit and the Indian mind in general, the book also contained a strong denunciation of Buddhism, which Schlegel—based on his limited reading—characterized as a form of pantheism: “a frightening doctrine which, by its negative and abstract, and thus erroneous, idea of infinity, led by necessity to a vague indifference toward being and non-being.”6 It’s hard to tell where Schlegel got the idea that Buddhism is pantheism, but his own earlier Romantic ideas about religion definitely were pantheistic. So, in attacking Buddhism, he was actually distancing himself from his earlier Romantic pantheism. This fact was underscored by the second major event in Friedrich and Dorothea’s life in 1808: their conversion to Catholicism.

Little is known as to why they abandoned their Romantic religious ideas. One modern theory is that their stay in Paris had destroyed their earlier faith in freedom and progress. At any rate, Friedrich’s only explanation to their friends—incredulous over the conversion—was that “To become Catholic is not to change, but only first to acknowledge religion.”7

It also enabled him to find steady employment. As a Catholic, he qualified for—and, in 1809, received—a position in the Austrian civil service. Moving with Dorothea to Vienna, he edited an anti-Napoleonic newspaper and aided the Austrian diplomat, Metternich, in drawing up plans to re-establish a conservative order in Germany after Napoleon’s defeat.

At the same time, Schlegel began a second career as a public speaker, giving lecture series in Vienna on such topics as history and literature, and the philosophy of life, literature, and language. In 1823, when he and Dorothea published his collected works, they omitted Lucinde from the collection.

He died while on a speaking tour, in Dresden, in 1829. After his death, Dorothea moved to Frankfurt am Main, where she settled with her younger son, Philippe Veit, a painter in the Nazarene movement. She died in 1838.

In 1835, however, a leader of the Young German movement, Karl Gutzkow, had published Lucinde for a second time, together with Schleiermacher’s defense of the book (see below). Even though—or perhaps, because—these books sparked another storm of controversy, they became rallying texts for the movement: an example of how early Romantic ideas, even when renounced by the early Romantics, were adopted by succeeding generations and given an extended second life.

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834)

Born in Breslau, Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher was the son of a clergyman in the Reformed church. His early education was with the Moravian Herrnhutter Brotherhood, the same Pietist group to which Novalis’ father belonged. Suffering from growing bouts of skepticism about Christian doctrine, he transferred to the university at Halle, where he nevertheless majored in theology, with philosophy and philology as minors.

He passed his clerical exams in Berlin in 1790, but did not immediately apply for a position with the church. Instead, he worked as a private tutor for three years, after which he was fired for sympathizing with the French Revolution. During this period he began studying Kant in earnest, only to grow critical of Kant’s rationalist approach to religion. After reading Herder’s writings on Spinoza (see Chapter Three), he began composing essays on religion that combined Herder’s interpretation of Spinoza with what he still saw as worthwhile in Kant’s thought. These essays, though, were rather dry, and attracted little attention.

In 1794 Schleiermacher took on his first clerical position, as a pastor in Landsberg, and then in 1796 he was appointed chaplain at the Charité hospital in Berlin. His stay in Berlin marked his blossoming as an original religious thinker. Historians of religion credit his chaplaincy for his growing appreciation of the role of feeling in a life of faith. Historians of philosophy credit his exposure to the intellectual salons of Berlin for his growth as a thinker. He himself described the discussions at the salons as “the most colorful hurly-burly of arguments in the world.”

In 1797, at the Herz salon, he met Friedrich Schlegel and, as noted above, the two became housemates. Their ongoing discussions led Schlegel to deepen his appreciation of religion—up to that point, he had been something of an atheist—at the same time leading Schleiermacher to realize that Schlegel’s ideas on art could help him articulate his own understanding of what it means to be religious in a universal rather than a strictly Christian sense.

The fact that Schleiermacher was straddling the divide between two worlds, religious institutions and the intellectual salons, put him in an ideal position to act as an interpreter between the two. His friends at the salons began urging him to put his ideas on religion on paper. At first, he simply composed fragments for Athenäum. Then, in 1798, Henriette Herz presented him with “a little box for your thoughts.” From November of that year until March of the following year he was called to Potsdam on a commission, a period away from his friends that gave him time to compose what was to become the defining book on Romantic religion: Talks on Religion for Its Cultured Despisers.

As the title indicates, the book was intended to defend religion to those who, in the salons, had come to view it with disdain. We will discuss the Talks in more detail in Chapter Five. Here we will simply note that the book argued, not for any specific religion, but for a transcendental idea of religion that had to be true for all people at all times and in all cultures. It contained two definitions of religion that were to become distinctive features of Romantic religion: One, religion is a matter of aesthetics: “a taste and sensitivity for the infinite.” Two, religion is not a relationship between human beings and God; it is “a relationship between human beings and the universe.”

The fact that the Talks displayed a knowledge not only of modern philosophy but also of modern science added to the book’s appeal. It was to go through many printings during Schleiermacher’s lifetime, and was widely read on both sides of the Atlantic.

In 1799, Schleiermacher and Schlegel embarked on what was to have been a long-term joint project: the retranslation of all of Plato’s dialogues into German. But this, too, was a project in which Schlegel quickly lost interest, a fact that led to a cooling in Schleiermacher’s feelings toward him. The latter nevertheless continued the translations on his own, and although he didn’t complete all the dialogues, he managed to publish a large number of them in the years 1804–1828. His experience with the project led him to develop theories on language, translation, and hermeneutics—or the science of interpretation—that were to exert great influence even into the 21st century. In fact, he is often regarded as one of the founders of hermeneutics, famous for first articulating what is called the hermeneutic circle: that to understand the parts of a text, you have to first understand the whole; but to understand the whole, you first have to understand the parts. The art of hermeneutics lies in working one’s way back and forth between these two requirements.

Meanwhile, Schleiermacher had become involved with two scandals. The first was the uproar surrounding Lucinde. In 1800 he wrote a novel of his own, Confidential Letters Concerning Friedrich Schlegel’s Lucinde, in which he defended Lucinde as a holy book. Then, in 1804, his own seven-year affair with a married woman—Eleonore Grunow, the wife of a Berlin clergyman—came to light, forcing him to flee Berlin. For a few years, he lectured at the university in Halle, where he was accused of atheism, Spinozism, and pantheism. Nevertheless, the university officials supported him, and his lectures remained popular. In 1806 he published a short literary dialogue, Christmas Eve, which extolled religion as a matter of the heart that should be centered on the fellowship of the family rather than on the state.

When, in 1807, Halle fell to Napoleon’s forces, Schleiermacher returned to Berlin. There he soon married Henriette von Willich, the young widow of one of his friends, and received an appointment as a preacher at Trinity Church.

In 1810, he played a part in the founding of the University of Berlin, where he was appointed as professor of theology. In 1811, he was appointed to the Berlin Academy of Sciences. In spite of his academic duties, he continued to preach every Sunday to appreciative crowds.

Also in 1811, he wrote A Brief Presentation of Theological Studies in which he outlined a course of studies that would prepare pastors to meet the needs of the modern world. The course was considered revolutionary at the time in calling for pastors to be conversant with the latest advances in philosophy and psychology. In line with this program, he lectured at the university not only on subjects obviously dealing with theological issues—such as New Testament exegesis and the life of Jesus—but also on dialectics, aesthetics, psychology, pedagogy, the history of philosophy, hermeneutics, translation, and politics. His forays into these areas, however, brought him into conflict with professors in other departments of the university who resented his invading their turf.

Over the years, as the Talks on Religion continued to go through several printings, Schleiermacher would cite these later editions as proof that he had not abandoned his earlier views. Nevertheless, he kept making changes in the book that steered it away from a universal Romantic orientation and toward a more specifically Christian one. For example, his original definition of religion as “man’s relation to the universe” became “man’s relation to the Highest.” And in place of a passage in the first edition arguing that, given the infinite nature of the universe, humanity would have to invent an infinite number of religions, all equally valid, he simply stated that religion is “the sum of all man’s relations to God.”

Most important, he entirely recast his discussion of the concept of “God.” In the first edition he explained this concept as only one possible product of the religious imagination—and not even the highest product at that—whereas in later editions he insisted that there was no way to conceive of the universe as a whole without also conceiving it as existing in God.

This was a major retreat from his earlier espousal of Romantic religion. Despite this retreat, though, he remained liberal both in politics and in his interpretation of Christian doctrine. In the area of politics, he campaigned for the right of the Church to determine its own liturgy without interference from the state. In the area of doctrine, his most comprehensive book on theology, The Christian Faith (1821–22), became the founding document of liberal Protestant theology in the 19th century. This book focused on faith as a feeling of dependency on God that was transmitted, not through the Bible or through rational argument, but through a more personal contact with Jesus Christ via the fellowship of the Church. By taking this position, Schleiermacher returned somewhat to his Pietist roots. As a result, he found himself fending off attacks on two sides—from traditional doctrinal theologians on the right and from rationalists on the left—for the rest of his life. One of the rationalist attacks, from Hegel, we will discuss in Chapter Six.

Schleiermacher’s only son, Nathaniel, died in 1827, an event that, he said, “drove the nails into my own coffin.” He lived, however, for another seven years, dying of pneumonia in 1834.

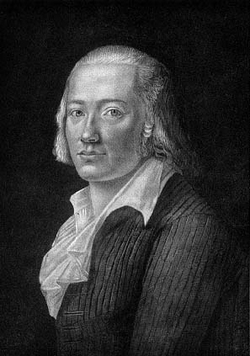

Friedrich Hölderlin (1770–1843)

A native of Swabia, Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin was the son of a manager of Lutheran Church estates who died when young Friedrich was two. His mother soon remarried, but the stepfather died when Friedrich was nine. The double loss left both mother and son emotionally scarred. Because of the madness that Hölderlin suffered later in life, the facts of his early childhood have been subjected to intense posthumous scrutiny as a likely source for his eventual breakdown. The bare facts seem to indicate that his mother became gloomy and pious, eager to offer her son to God as a form of penance; that he was sensitive and prone to extreme swings of mood; and that her attempts to force some stability and piety on him, even well into his adulthood, exacerbated his condition.

At her insistence, in 1788 he entered the seminary at Tübingen, where he roomed with Hegel and Schelling. Because both of his roommates went on to become the preeminent philosophers of 19th century Germany, there has been some speculation as to what influence the three had on one another in their seminary days. Schelling—not one to easily give credit to other thinkers—regarded Hölderlin as his mentor in philosophical matters at least until 1795.

The curriculum at the Tübingen seminary was dedicated to finding harmony between Christian doctrine and the classics. Thus Hölderlin, in addition to joining a poetry club, wrote theses on the history of the fine arts in Greece and on the parallels between the Proverbs of Solomon and Hesiod’s Works and Days. He soon realized, however, that his interests lay with the ancient Greeks and not with the Church. He petitioned his mother to transfer to a university, but she refused, so he completed his studies and passed his clerical exams in 1793.

Despite her pressure to serve God and take a clerical position, Hölderlin began to pursue the intellectually more independent, if financially riskier, life of a private tutor. Had his mother wanted, she could have spared him the need to look for work, because his father had left him a substantial patrimony. She, however, intimated that the patrimony was very meager; even in later years when he was in extreme financial need, she would spare him no more than a pittance at a time. Only after Hölderlin’s death was it discovered that, on paper at least, he had been a rich man all along.

With the help of Schiller, who was to be his hero and patron for several years, Hölderlin obtained a position in 1793 as tutor to the son of a widow who shared his literary interests. During this period he began writing his novel, Hyperion, which was to go through several drafts before its publication, in two parts, in 1797 and 1799.

In 1794, Hölderlin accompanied his pupil to the university at Jena, where Fichte had just taken up a position. Hölderlin signed up for a full schedule of lectures, but soon found himself so enthralled with Fichte’s teachings—and especially with Fichte’s espousal of the cause of freedom—that he neglected his other subjects. While in Jena, he also met Novalis, who was attending Fichte’s lectures, too.

However, like Novalis, Hölderlin soon began to have doubts about Fichte’s foundationalist approach to philosophy, and no later than May 1795, he wrote down a short piece, Being and Judgment. This was the first written expression anywhere of what was to become the basic Romantic viewpoint: that nature, in the form of Pure Being, is the original Absolute, embracing both subject and object, and transcending all forms of dualism; and that this Absolute can be comprehended, not through systematic reasons, but only aesthetically—i.e., through the feelings. He communicated some of these ideas to Schelling in 1795.

In 1796 he obtained a new position as tutor in Frankfurt am Main for the children of a banker, Jakob Gontard. Quickly he discovered a kindred sensitive soul in Gontard’s wife, Susette (1769–1802), and the two began an affair that lasted until 1800. Susette Gontard, however, was more than a mistress or lover for Hölderlin. She was both the supportive presence that he had lacked in his early life and the muse to inspire him to greater feats as a writer. Critics note that only during this period did Hölderlin begin to show true genius as a poet. He addressed many of his poems to Susette, calling her Diotima after the mysterious woman who was Socrates’ teacher in matters of love. He also rewrote Hyperion so that the character of Diotima, Hyperion’s lover, became a transfigured version of Susette: calmly attuned to nature and deeply wise.

While at Frankfurt, Hölderlin also helped his old roommate, Hegel, find a job with a nearby family, although little is known of the philosophical discussions they may have had at this time.

Jakob Gontard discovered the affair in 1798, and Hölderlin was summarily dismissed. He settled nearby, in Homburg, so that he and Susette could continue meeting clandestinely on an irregular basis.

While at Homburg, Hölderlin revived a friendship with another old schoolmate, Isaak von Sinclair, who was to provide him with financial and emotional support off and on for the next several years. In fact, the two of them, together with other friends, formed an intellectual circle that some historians have termed the Homburg circle, which was loosely connected with the Jena circle that had formed at the same time.

However, Hölderlin was not enamored of the journal Athenäum that the Schlegel brothers were producing. In addition to beginning a major new literary project, a drama on the suicide of Empedocles, he started writing philosophical pieces in preparation for a journal that he proposed to edit. One of the pieces was a review of Schleiermacher’s Talks on Religion. Ironically, despite Hölderlin’s differences in temperament from Friedrich Schlegel, his review came to some of the same conclusions as Schlegel’s own review of the book: that because religion is concerned with a feeling for the infinite, and because language is finite, the only proper language for religion must deal in myths and allegories, as these are the only modes of speech that clearly point to something beyond themselves. During the few years of relative sanity remaining to him, Hölderlin was to write many religious poems in a prophetic tone that combined the myths and images of classical Greece with those of the Bible into a pantheism and polytheism of his own.

1799 proved to be a critical year for Hölderlin. His efforts to find backing for his new journal met with no success and he could find no other work near Frankfurt, which meant that the affair with Susette had to end. His old mood swings began to recur, and Sinclair was often called on to intervene when his periodic shouting rages and “strumming on his piano” provoked angry threats from his neighbors. Feeling rejected on all sides, Hölderlin abandoned his philosophical writings and decided to devote his writing talents totally to poetry. He accepted work outside of Germany, first as a tutor to a family in Switzerland, then as a tutor to the family of the Hamburg consul in Bordeaux. In neither case, though, was he stable enough to hold his position for long. In both cases, he walked to his new position and then back home to Germany alone.

On his return from France, in 1802, he received a letter from Sinclair with news that Susette had died of measles. The news of her death, combined with the rigors of the trip, left Hölderlin a broken man, both physically and mentally. Schelling, writing to Hegel after meeting Hölderlin at this time, diagnosed his state as “derangement.” Sinclair arranged for Hölderlin to obtain medical treatment with a physician who found that reading Homer to Hölderlin in the original Greek was most effective in calming his mind. As Hölderlin’s condition began to improve, Sinclair found him work that would not tax his health.

Despite his brittle emotional state, Hölderlin was able to complete, and get published, his translations of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and Antigone. The translations were criticized at the time for being too strange—Hölderlin had hewn closely to the syntax of the Greek—but eventually they became more widely appreciated. He also continued work on multiple drafts of his tragedy, The Death of Empedocles, but the work remained unfinished.

He also put into writing, both in essays and poems, his thoughts on tragedy. True to his love for the Greek tradition, he saw tragedy as intimately connected with religion. Because he also felt that religion was primarily a matter of feeling, his writings on tragedy provide a window onto his feelings at this time.

A tragic poem, he said, is a metaphor of a particular intellectual point of view: “the awareness of being at One with all that lives.” Many people would find this awareness comforting rather than tragic, but Hölderlin’s view of Oneness was strongly colored by his emotional instability. Only during manic periods did he feel at One with the divine in nature, but while manic he had no understanding of what he was doing or saying. Only when the mania had passed could he understand what had happened, but that understanding was accompanied by a dark sense of isolation and despair. In his words,

“The representation of the tragic is mainly based on this, that what is monstrous and terrible in the coupling of god and man, in the total fusion of the power of Nature with the innermost depth of man, so that they are One at the moment of wrath, shall be made intelligible by showing how this total fusion into One is purged by their total separation.”8

Hölderlin’s poetry during this period moved into new modes of expression, very intense and very modern in their disjointed syntax and striking imagery. One of the hymns from these years ends with a passage of warning: To communicate the divine was to play with lightning.

Yet, poets, for us it is fitting to stand

bareheaded beneath God’s thunderstorming,

to grasp the Father’s ray, the Father himself, with our own hand

and to present to people the heavenly gift,

swaddled in song.

For if only we are pure in heart,

like children, with our hands unburdened with guilt,

the Father’s ray, the pure, will not scorch

and, though deeply convulsed—the sorrows of the Stronger One,

compassionate, the tumultuous storms of

the God when he draws near—the heart will stand fast.

But, ah me! When of

Ah me!

And so now I say

that I approached to see the Heavenly.

They themselves cast me down, deep down

below the living, into the darkness,

false priest that I am, to sing

the warning song of those who know.

There

In 1805, Sinclair was charged with high treason for plotting to kill the Grand Duke of Württemberg, and Hölderlin was implicated in the case. The shock of the accusations apparently drove him over the edge. Although the charges against both men were eventually dropped, Hölderlin was clearly in need of intensive medical care, and Sinclair was no longer in a position to help. In 1806 Hölderlin was committed, much against his will, to the Autenrieth asylum in Tübingen, where treatments included belladonna, digitalis, straitjackets, masks to stop patients from screaming, and forced immersions in cold water inside a cage. Friedrich Schlegel tried to visit him during this period, but was told that Hölderlin was “not presentable.”

Meanwhile, Ernst Zimmer, a carpenter living nearby, learned of Hölderlin’s plight. Having been deeply impressed by Hyperion, he convinced the doctors at the asylum that Hölderlin would respond better to a quiet domestic environment. So, in 1807, Hölderlin was released into his care. Zimmer and his family provided Hölderlin with a quiet tower room in their house in Tübingen, overlooking the Neckar River. Doctors expected Hölderlin to live for no more than three more years, but the Zimmer family ended up looking after him for another 36.

It was to be a life of leaden calm after the passing of the storm. At first, Hölderlin began drafting a continuation of Hyperion, in which Diotima—who had died of a broken heart in Part Two of the novel—speaks from the afterlife, but he soon abandoned the project. No longer giving vent to his wild mood swings, he would address visitors with exaggerated politeness and formality, writing short poems at request. A few of the more affecting ones hinted at a sadness he didn’t dare express, but otherwise they were nothing but surface. He would sign them “Scardinelli, or something of the sort,” and give them fictional dates, such as 1648 or 1759. Aside from one visit, from his step-brother, his family—including his mother, who died in 1828—never came to see him. They did, however, insist that Zimmer take Hölderlin’s poetry notebooks from him for them to put in safekeeping—a harsh but perhaps wise move.

Although there was some appreciation of Hölderlin’s writings during the 19th century—Nietzsche, for one, was an avid admirer of Hyperion—only in the early 20th century were his collected poems published. Many poets at the time, including Rilke and Celan, were struck by the originality of Hölderlin’s language and imagery, and came to regard him as one of their own: a Symbolist, an Imagist, even a Surrealist well before his time. Since then, his reputation as a poet has continued to grow to the point where many poets and critics regard him as one of the premier poets that Europe has produced.

His philosophical writings did not come to light until the mid-20th century, so only recently have scholars begun to appreciate him as a Romantic philosopher as well as a poet.

Because of the renewed interest in Hölderlin’s writings, there have been many efforts at posthumous psychoanalysis to diagnose his final breakdown. The more common verdicts include schizoid psychosis, catatonic stupor, and bipolar exhaustion. However, what is perhaps the most perceptive diagnosis was a comment that Zimmer once made about Hölderlin’s condition to a friend: “The too-much in him cracked his mind.”

He died of pulmonary congestion in 1843.

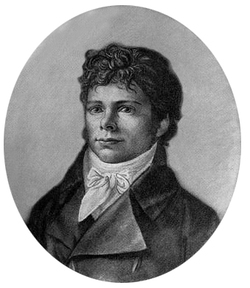

Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854)

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, the son of Pietist parents, was born in Württemberg not far from Hölderlin’s birthplace. In fact, the two first became friends at an early age when both were in Latin school, where Hölderlin protected the young Schelling from bullies.

A very precocious child, Schelling was admitted to the Tübingen seminary at the age of 16, four years short of the normal age of enrollment. There, as noted above, he roomed with Hölderlin and Hegel, both of whom sparked his interest in revolutionary politics and philosophy. In 1794, at the age of 19, he published his first book on philosophy, before completing his theological degree in 1795.

Schelling’s early philosophical writings were well received, and even though he kept shifting his philosophical positions throughout his career, his reputation among German intellectuals and academics remained high. The constant revisions in his thought from one book to the next inspired Hegel later to remark sarcastically that Schelling had conducted his philosophical education in public.

The underlying tension that propelled the evolution of Schelling’s thought can be illustrated by two declarations he made in 1795. Writing in Of the I as the Principle of Philosophy or On the Unconditional in Human Knowledge, a treatise that was intended to offer both support and a corrective for Fichte’s philosophy, he declared, very much in Fichte’s spirit, “The beginning and end of all philosophy is freedom!” However, in a letter to Hegel written in the same year, he declared, “Meanwhile, I have become a Spinozist!” Apparently, under Hölderlin’s influence, he had been drawn to Spinoza’s metaphysical system built on a principle of Absolute Being that transcended all dualities. However, in Spinoza’s system, as we will see in Chapter Four, only God is free. People have no freedom of choice at all. The burden of Schelling’s philosophical efforts over the next several years lay in reconciling these two irreconcilable positions on freedom. Despite his early enthusiasm for Fichte, Spinoza was to win.

In 1796, Schelling was employed as a tutor to two sons of an aristocratic family. A trip to Leipzig with his charges in 1797 exposed him to modern developments in science, particularly biology and chemistry. This exposure inspired him to take up an independent study of all the sciences. For many years, he kept abreast of the latest scientific developments, and during the years 1799 to 1804 he wrote several systematic treatises that tried to incorporate the sciences into the Romantic philosophical view of the universe as an infinite organic unity, founded on an Absolute principle of Identity transcending all dichotomies, even those of matter and energy, and of self and not-self.

It was during the Leipzig trip that Schelling also met Novalis and the Schlegel brothers for the first time.

In 1798, at the age of 23, he was appointed an extraordinary professor of philosophy at Jena—the “extraordinary” meaning that the appointment was funded by the Duke of Saxe-Weimer, who offered the position to Schelling apparently at Goethe’s suggestion. Thus began Schelling’s involvement with the Jena circle.

At first, his relations with Fichte were cordial. But, unlike Schlegel and Novalis, who quickly broke with Fichte over philosophical differences but were able to remain friends with him on a personal level, Schelling’s philosophical split with Fichte was somewhat protracted; when the break finally came, in 1801, it was total. In a letter to Fichte, demanding that the latter no longer regard him as a collaborator, Schelling wrote, “I am not your enemy, although you are in all probability mine.” Once the line was drawn, there was no possibility of friendly communication between the two. This pattern was to repeat itself several years later, in 1807, when Schelling had a particularly bitter break with Hegel.

In 1800, Schelling had become engaged to Auguste Böhmer, Caroline Schlegel’s daughter from a previous marriage. Auguste, however, died of dysentery later the same year. As Schelling and Caroline comforted each other over Auguste’s death, they fell in love. Caroline asked her husband, August, for a divorce, on the grounds that she had finally met the love of her life, and August magnanimously consented.

The townspeople of Jena, though, were not appeased. Rumor had it either that Caroline had poisoned her daughter to have the young Schelling for herself, or that Schelling was the one who had administered the poison. August stoutly defended the couple, but the scandal refused to die down, and the couple didn’t feel safe to marry in Jena. So in 1803, Schelling took a position at a new university at Würzberg, and the couple was finally married. As noted above, August Schlegel also left Jena in the same year; the departure of these three, the last remaining members of the Romantic circle in Jena, marked the end of early Romanticism. The year 1803 also marked Schelling’s last encounter with Hölderlin. He never visited Hölderlin during the latter’s final illness, and didn’t attend his funeral in 1843.

In 1806, Würzberg was annexed by Catholic Austria; Schelling, a Protestant, lost his job. So he moved to Münich, where he was offered a post as a state official with the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities; later, he was also appointed to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

In 1809, he published the last iteration of his philosophy to appear during his lifetime: Philosophical Investigations on the Essence of Human Freedom. In this treatise, he argued that the idea of freedom of choice lay at the root of all evil, and that only God was free. Virtue, he said, lay in obeying the impulses of one’s nature, because the source of that nature was divine. But because one could not choose one’s nature, this meant that virtue had no freedom.

Thus the retreat from his earlier position—that philosophy begins and ends in freedom—was complete. God may be free in the beginning and end, but human beings have no genuine freedom at any point in the timeline.

As the book was being readied for publication, Caroline died. Many commentators have suggested that her death killed Schelling’s spark to keep on publishing. Nevertheless, he married again, in 1812, to one of Caroline’s friends, Pauline Gotter, and the two apparently had a calm and happy married life. At the same time, Schelling continued to teach and to develop his thoughts on philosophy. Although he wrote prolifically, he never published his writings—perhaps because his positions continued to evolve, perhaps because he sensed that Hegel was ready and eager to pounce on whatever he might put into print.

The general thrust of his thought during this period was anti-foundationalist. He came to see that the search for a first principle on which to base all philosophy was a big mistake; the fact that an idea may be coherent in the realm of thought doesn’t prove its truth in the realm of reality. Instead, he felt, religion and mythology were the true positive complements to the negative approach of logical and speculative philosophy. All truth, in his eyes, begins with the fact that God is free from all constraints, including the constraints of reason.

Hegel, who had been lecturing to great acclaim at the University of Berlin, died suddenly in 1831. Nevertheless, his influence continued to dominate academic circles in Berlin. The king of Prussia, concerned about Hegel’s unorthodox views and their impact on the Prussian public, summoned Schelling to Berlin to lecture on philosophy and religion to help “stamp out the dragon-seed of Hegelian pantheism.” The fact that the king saw the fate of the Prussian state as resting on Schelling’s lecture series, which he delivered in 1841–42, gives an indication of the perceived importance of philosophy in Germany at the time.

The lectures, however, were a failure. Schelling’s increasingly conservative views on God and philosophy were completely out of step with the times, and his close association with the powers that be, both in Bavaria and Prussia, gave the impression that he was little more than their lackey. If anything, the lectures had a reverse impact, in that they inspired young left-wing Hegelians, such as Karl Marx, to regard the abolition of religion as the first order of business in bringing about human freedom and a just society.

However, the lectures were also attacked by traditional Christian thinkers. In 1843, Heinrich Paulus, a theologian who had developed an animosity for both Hegel and Schelling over the years, published pirated transcripts of the lectures to expose Schelling’s views as incoherent. Schelling tried, but failed, to have the books banned. And so he stopped lecturing for good.

The conservative drift in his philosophy paralleled a similar drift in his political views. In 1792, he had celebrated a major victory in the French Revolution. In 1848, when another wave of revolutions swept through Europe, he suggested angrily that all the rioters be shot.

He died in Switzerland in 1854. His sons, in the years 1856–58, finally published authorized versions of the Berlin lectures, in four volumes.

Although Schelling’s reputation as a philosopher quickly went into decline, his observations on the disjoint between thought and actuality—that just because reason says we have to think about things in a certain way doesn’t mean that things actually are that way—was to provide inspiration for many modern and postmodern movements in European culture.

Shaping the Romantic Experience

Unlike the Buddha, who taught religion as a matter of skill—the skill of finding a lasting and blameless happiness—all five of these Romantic thinkers taught religion as a matter of aesthetics. In the language of their time, this meant two things: (1) that religion dealt with feelings and direct experiences, rather than reason; and (2) that it was an art. In line with their personal views on art, religion-as-art had to be expressive. In other words, religious ideas cannot describe the way things are. Instead, they can only express the feelings of the individual who has a religious experience.

Their position on this issue, of course, contains a paradox: It describes how religion has to act, while at the same time saying that descriptions about religion are not genuine. In Chapters Four through Seven we will explore this paradox and its long-term effects.