Introduction

Dukkha — the experience of stress, pain, suffering — is not a simple thing. As the Buddha once observed, we respond to its complexity in two ways:

§ 1. “And what is the result of stress? There are some cases in which a person overcome with pain, his mind exhausted, grieves, mourns, laments, beats his breast, and becomes bewildered. Or one overcome with pain, his mind exhausted, comes to search outside, ‘Who knows a way or two to stop this pain?’ I tell you, monks, that stress results either in bewilderment or in search.” — AN 6:63

The problem is that the bewilderment often guides the search, leading to more suffering and stress. To resolve this dilemma, the Buddha devoted his life, after his Awakening, to showing a reliable way to the end of stress. In summarizing the whole of his teaching, he said:

§ 2. “Both formerly and now, it is only stress that I describe, and the cessation of stress.” — SN 22:86

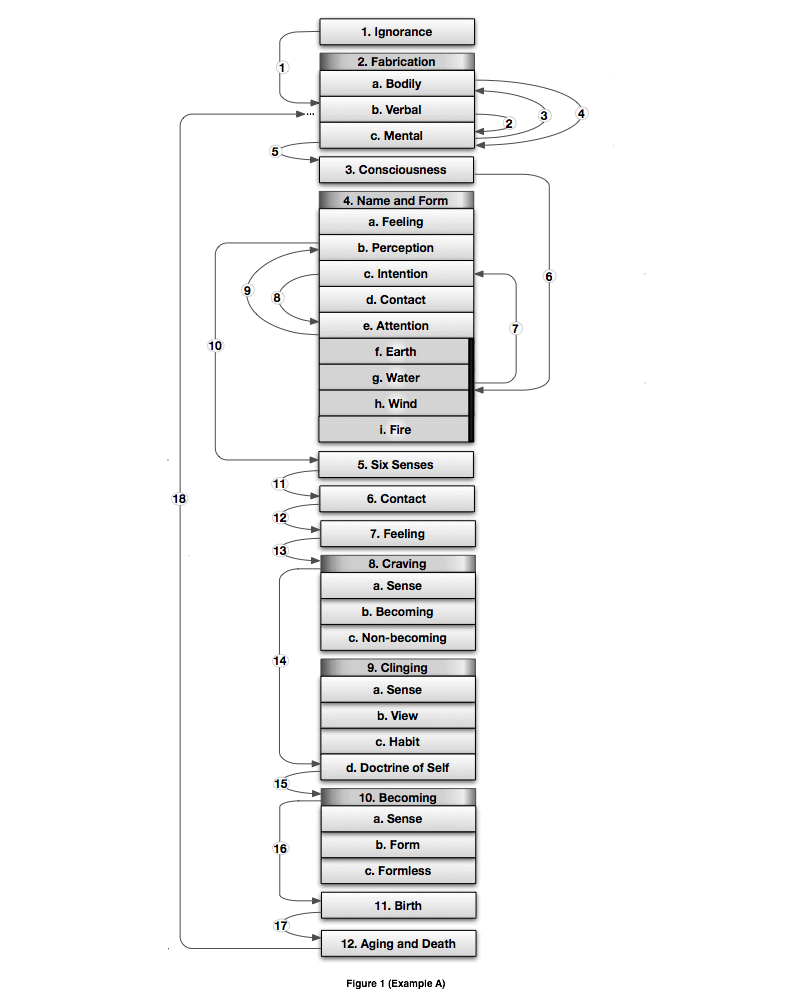

These were the issues he taught for 45 years. In some cases, he would give a succinct explanation of stress and its cessation. In others, he would explain them in more detail. His most detailed explanation is called dependent co-arising — paṭicca samuppāda. This detailed summary of the causal factors leading up to stress shows why the experience of suffering and stress can be so bewildering, for the interaction among these factors can be very complex. The body of this book is devoted to explaining these factors and their interactions, to show how they can provide focus to a path of practice leading to the ending of stress. But first, here is a list of these factors, enough to give a general sense of the shape of dependent co-arising, and to show how unwieldy it can seem. The factors will be explained in more detail in the body of the book. Here they are numbered starting with the most fundamental factor, ignorance, for ignorance is the most strategic factor in causing the other factors to contribute to stress.

- Ignorance: not seeing things in terms of the four noble truths of stress, its origination, its cessation, and the path to its cessation.

-

Fabrication: the process of intentionally shaping states of body and mind. These processes are of three sorts:

- Bodily fabrication: the in-and-out breath

- Verbal fabrication: directed thought and evaluation

- Mental fabrication: feeling (feeling tones of pleasure, pain, or neither pleasure nor pain) and perception (the mental labels applied to the objects of the senses for the purpose of memory and recognition).

- Consciousness at the six sense media: the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and intellect.

-

Name-and-form: mental and physical phenomena.

- Mental phenomena include:

- Feeling

- Perception

- Intention

- Contact

- Attention

- Physical phenomena include:

- Earth (solidity)

- Water (liquidity)

- Wind (energy and motion)

- Fire (warmth)

- Mental phenomena include:

- The six internal sense media: the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and intellect.

- Contact at the six sense media. (Contact happens when a sense organ meets with a sense object — for example, the eye meets with a form — conditioning an act of consciousness at that sense organ. The meeting of all three — the sense organ, the object, and the act of consciousness — counts as contact.)

- Feeling based on contact at the six sense media.

-

Craving for the objects of the six sense media. This craving can focus on any of the six sense media, and can take any of three forms:

- Sensuality-craving (craving for sensual plans and resolves).

- Becoming-craving (craving to assume an identity in a world of experience)

- Non-becoming-craving (craving for the end of an identity in a world of experience).

-

Clinging — passion and delight — focused on the five aggregates of form, feeling, perception, fabrication, and consciousness. This clinging can take any of four forms:

- Sensuality-clinging

- View-clinging

- Habit-and-practice-clinging

- Doctrine-of-self-clinging

-

Becoming on any of three levels:

- The level of sensuality

- The level of form

- The level of formlessness

- Birth: the actual assumption of an identity on any of these three levels.

- The aging-and-death of that identity, with its attendant sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, and despair.

Even a cursory glance over these twelve factors will show two of the major ways in which dependent co-arising is an unwieldy topic: (1) The factors seem to fit in different contexts and (2) many of the sub-factors are repeated at seemingly random intervals in the list.

In terms of context, some of the factors seem more psychological, referring to events within the mind in the present moment, whereas others seem more cosmological, referring to events over the course of a lifetime, and even many lifetimes. And in the centuries after the Buddha’s passing, there have been many attempts to make the list less unwieldy by fitting all the factors into a single interpretation, as referring either to events occurring right now or over a long course of time.

There have even been attempts to — literally — impose a shape on the list as a whole. That shape is a circle, and there are two primary ways in which the circle has been described. The first — an idea proposed in medieval India — is as a wheel, with the sorrow, etc., of aging-and-death leading to more ignorance and so on to another round of suffering and stress. The second circle — proposed in medieval China — is a circle of mirrors surrounding a lamp, with each mirror reflecting not only the light directly from the lamp, but also the lamplight reflected from other mirrors.

In Chapters One and Two we will discuss the formal reasons for why these simplified images are inadequate as depictions of dependent co-arising. But here we will offer a thought-experiment to show how they are also inadequate for depicting an everyday, concrete example of how people suffer.

For the sake of this experiment, assume that you are walking to your parents’ home on a Friday evening after a long day’s work. The upcoming weekend is a holiday, and your parents are hosting a dinner for your extended family. Your uncle will be at the dinner, and this fact has you upset: He has long been an alcoholic and has been very abusive to you and your mother ever since you were a child. The factors of dependent co-arising — inserted in the discussion as numbers drawn from the above list — can be applied in three time frames to show different ways in which you might create suffering and stress around this event.

In each of these examples, assume (1) that you are operating in ignorance — i.e., you are not thinking in terms of the four noble truths, and instead are looking at your situation in light of your personal narratives about the family situation and your own place in it.

As you walk to the door of your parents’ house, thinking about the situation (2b — verbal fabrication), you pull up memories of things your uncle has done in the past (2c — mental fabrication). This provokes anger, causing your breathing to become labored and tight (2a — bodily fabrication). This makes you uncomfortable (2c — mental fabrication), and you are aware of how uncomfortable you feel (3 — consciousness). Hormones are released into your bloodstream (4f through 4i — form). Without being fully aware that you are making a choice, you choose (4c — intention) to focus (4e — attention) on the perception (4b) of how trapped you feel in this situation. Your consciousness of this idea (5 and 6 — mental contact) feels oppressive (7 — feeling). You want to find a way out (8 — craving). At this point, you can think of a number of roles you could play in the upcoming dinner (9d and 10 — clinging and becoming). You might refuse to speak with your uncle, you might try to be as unobtrusive as possible to get through the dinner without incident, or you might be more aggressive and confront your uncle about his behavior. You mentally take on one of these roles (11 — birth), but unless you keep your imaginary role actively in mind, it falls away as soon as you think of it (12 — aging and death). So you keep thinking about it, evaluating how your parents will react to it, how you will feel about it, and so on (2b — verbal fabrication). Although the stress of step (12) in this case is not great, the fact that your role has to be kept in mind and repeatedly evaluated is stressful, and you can go through many sequences of stress in this way in the course of a few moments.

You have been walking to your parents’ house with the above thoughts in mind (2 through 4), already in a state of stress and unhappy anticipation. You knock on the door, and your uncle answers (5 and 6) with a drink in his hand. Regardless of what he says, you feel oppressed by his presence (7) and wish you were someplace else (8c). Your mother makes it obvious that she does not want a scene at the dinner, so you go through the evening playing the role of the dutiful child (9c, 10a, 11). Alternatively, you could decide that you must nevertheless confront your uncle (again, 9c, 10, and 11). Either way, you find the role hard to maintain and so you break out of the role at the end of the dinner (12). In this way, the entire evening counts as a sequence of stress.

Instead of dropping the role you have taken on, you assume it for the rest of your life — for instance, as the passive, dutiful son or daughter, as the reformer who tries to cure your uncle of alcoholism, or as the avenger, seeking retributive justice for the many hardships you and your mother have had to endure. To maintain this role, you have to cling to views (9b) about how you should behave (9c) and the sort of person you are or should be (9d). You keep producing (10) and assuming (11) this identity until it becomes impossible to do so any further (12). In this way, a full sequence of dependent co-arising could cover an entire lifetime. If you continue craving to maintain this identity (8b) even as you die, it will lead you to cling (9) to opportunities for rebirth (10 and 11) as they appear at the moment of death, and the full sequence of dependent co-arising could then cover more than one lifetime, leading to further suffering and stress on into the indefinite future.

As these scenarios show, there is no single, definitive time frame for the ways in which dependent co-arising can produce suffering and stress. A single sequence can last a mere moment or many years. However, even the longest sequence, to continue functioning, requires repeated loops of momentary sequences, as one maintains an identity through thinking about it (2b) and intentionally attending to whatever factors are needed to maintain it (4c and 4e). Thus, even though we may speak of a single sequence crossing over lifetimes, that sequence doesn’t yield stress only as it ends in aging-and-death, for it is maintained by myriads of momentary sequences that produce repeated stress at varying levels — sometimes more, sometimes less — all along the way.

To further complicate this picture, the factors within the sequence can feed back into one another before completing a full sequence. This is the meaning of the specific factors and sub-factors that occur in different positions within the sequence. Feeling, for instance, appears in at least four factors of the list (counting the suffering in factor 12 as a feeling as well). Consciousness, appears twice, as does perception. In each of these cases, a later appearance of the factor, instead of leading directly to the factor following it in the list, can be treated once more in the role it plays in an earlier appearance. (This fact accounts for the way in which the mind can spin through many cycles of thought before coming up with a definite decision to take action on a matter.) For example, a feeling of pain appearing in (7), instead of inevitably leading straight to craving, could be treated as a type of mental fabrication (2c) or as an event under name (4a). If, as a mental fabrication, it is subjected to further ignorance, that would simply compound the stress in the subsequent cycle through the causal change. A similar result would occur if, as an event under name, it is subjected to further inappropriate attention (4e), which is equivalent to ignorance. In terms of Scenario A, this would correspond to the point at which you feel oppressed at the prospect of going to the dinner. If you keep focusing on this feeling in an ignorant or inappropriate way, you simply compound the stress of your situation, enflaming the sense of oppression until it becomes unmanageable.

However, if the feeling in (7) is treated with knowledge as a type of mental fabrication (2c) or with appropriate attention (4e) — another synonym for knowledge — as an instance of name, that would redirect the sequence in a skillful way, reducing the amount of suffering and stress produced. For example, if — when you start feeling oppressed at the prospect of the upcoming dinner — you reflect on the fact that your labored breathing is causing unnecessary stress, you can stop to adjust your breathing so that it feels more refreshed (2a). You can think about the situation in different ways, seeing the dinner as an opportunity to develop skillful qualities of the path, such as right resolve and right speech (2b). You can remember the positive things that your uncle has done in the past, and your own personal need to think in that way (2c). You can make up your mind to do or say whatever seems most skillful in the situation (4c). In this way, you can defuse the sense of oppression and abort the particular sufferings it would have caused.

In this way, although the reappearance of feeling at different points in dependent co-arising has the potential for compounding the problem of stress and suffering, it also opens the opportunity for a particular sequence of suffering to be alleviated. The fact that a long sequence of dependent co-arising requires the repeated occurrence of many short sequences — full or partial — similarly offers the opportunity for unraveling it at any time, simply by unraveling any one of the short sequences.

For these reasons, it is best not to view dependent co-arising as a circle, for such a simplistic image does not do justice to the many different time frames simultaneously at work in the production of suffering. Nor does it do justice to the ways in which the complexity of dependent co-arising provides an opening for suffering to be brought to an end. A better image would be to view dependent co-arising as a complex interplay of many feedback loops that, if approached with ignorance, can produce compounded suffering or, if approached with knowledge, create repeated opportunities to redirect the sequence and dampen the experience of suffering or stress.

Of course, the untrained mind is changeable. Having once dealt with feeling in a knowledgeable way, it can revert to ignorance at any moment. However, the Buddha’s discovery on the night of his Awakening is that it is possible to train the mind in such a way that its tendency to ignorance can be eliminated once and for all. And a common theme in the strategies he employed in this training is that ignorance can be overcome by developing sustained knowledge of any of the factors of dependent co-arising. Here again, the complexity of dependent co-arising plays an important role in allowing this strategy to work. These points form the underlying theme for this book.

Chapter One explores the formal reasons for why the wheel image used to describe dependent co-arising is inadequate for understanding the problem of suffering and stress. This chapter also points out the practical advantages offered by the complexity of dependent co-arising, in that the complex interplay of its lines of causality means that the causal process as a whole can be unraveled by developing knowledge focused on any one of its factors.

Chapter Two explores the inadequacies of the circle of mirrors image by examining an underlying image that the Buddha himself used to describe dependent co-arising: the image of feeding. While the circle of mirrors suggests a harmlessly beautiful and static vision of dependent co-arising, the image of feeding reveals the inherent instability of dependent co-arising and the desirability of putting an end to the process. This chapter also explores the theme of feeding with reference to the way this theme was viewed in classical Indian thought, and discusses the Buddha’s strategic use of physical and mental feeding to lead the mind to a point where it no longer needs to feed. In other words, the causal process — as exemplified by feeding — can be converted from one that produces suffering to one that brings suffering to an end.

Chapter Three explores the practical aspects of points made in Chapters One and Two. On the one hand, it shows how specific practices in the Buddhist path are meant to bring knowledge to bear on specific factors of dependent co-arising. On the other, it shows how specific factors in dependent co-arising — particularly, fabrication and name-and-form — can be shaped into tools for use in the path to the end of suffering and stress. Once they have performed their functions as tools, these factors can be contemplated so as to abandon any remaining passion for them.

The upshot of this chapter is that a person aiming to put an end to suffering does not need to know all the ins and outs of dependent co-arising, because the practice can be completed by focusing on any one of its component factors. Once that one factor is understood, that understanding will spread to the other factors as well. Still, an appreciation of the complexity of dependent co-arising helps to explain why this is so. At the same time, a knowledge of its various factors gives a sense of the full range from which a focal point can be chosen, and an understanding of the practices the Buddha recommended with regard to each focal point assists in gaining the practical benefit this knowledge is intended to give.

Thus this book. The material is presented as a collection of readings from the discourses of the Pali Canon — our earliest record of the Buddha’s teachings — interlaced with discussions to bring out their most salient points. I have not attempted a complete discussion of all the relevant topics, for that would have created a book too complex to be of use. Instead, I have provided the discussions as food for further thought. Training the mind to feed itself in this way is an important step in using the teachings on dependent co-arising to attain their intended goal.